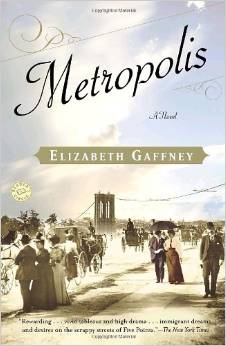

When a German immigrant—a stonemason who had worked on a cathedral in Hamburg—is falsely accused in post-Civil War New York City of arson and murder, he’s adopted by an Irish gang, the Whyos, and comes under the protection of Beatrice O’Gamhna, a tough, pretty, and capable young woman who carries an eye gouger. At that point you’re already held fast in the snaking twists and turns of Elizabeth Gaffney’s first novel, Metropolis (Random House), amid bigger-than-life characters bearing names such as Dandy Johnny, Maggie the Dove, and Luther Undertoe (aka the Undertaker). Danger lurks everywhere, and Beatrice protects the mason—an outsider and something of a naïf—by giving him a new identity as an Irishman called Frank Harris. He masters an Irish accent and constructs an elaborate past to match it. While he continues to dream of working high up on cathedrals, he finds himself laboring down in the sewers of New York—and this polarity takes on mythical symbolism as he struggles to move forward in the strange new world into which he has fallen. Part of the strangeness is the curious, odd-angled romance he has with Beatrice. Beneath its meticulously researched historical trappings of candle lanterns, horsehair sofas, and growlers of beer, Metropolis turns out to be focused on notably modern concerns—questions about identity, trust and mistrust, underworld manipulation, civic corruption, and especially social justice and racial and sexual equality. “America was what her parents had left her,” Beatrice reflects, bruised from yet another beating at the hands of Dandy Johnny—well aware that her world “wasn’t anyone’s American dream.” In mixing raw realism with fantasy, irony, and black humor, Metropolis conjures up a vision of women and men struggling to endure and prevail over poverty and brutalization. As the bond between Beatrice and Frank strengthens, the story line strongly comes to suggest that optimism in such a world is by no means the same thing as empty hope—particularly when the couple stands atop one tower of the Brooklyn Bridge, free at last from the terror of Dandy Johnny. Yet there is also an underlying sense throughout that in the grinding metropolis, one may be only “free to defy expectation, free to spit at fate, free to work the chaos in the system, free to fail.”

Gaffney has crafted an engrossing fable, smoothly told, fraught with suspense, and all the more poignant for the social issues it illuminates—issues that, as the book’s last lingering images suggest, must be resolved again and again by each succeeding generation.

— Nicholas Rinaldi, Elle magazine, March 2005