BROOKLYN RULES

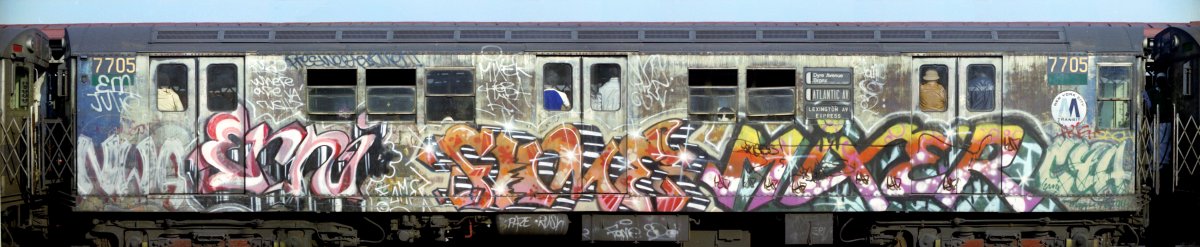

I grew up in Brooklyn in the 70s.

When I was five, the door of my house was hacked open with an ax in broad daylight on a Sunday afternoon.

My mother’s jewelry and my sterling silver piggy bank with leather ears were stolen, among other things.

The TV and the flatwear were trussed up in a mohair blanket by the door, to be picked up on a second visit.

(The parking sucks in my neighborhood, so I imagine the thief had to park some blocks away.)

That second phase of the larceny was interrupted by our return from the South Street Seaport.

They had Pete Seeger at the Seaport in those days. And the Fish Market. You could smell it.

I never thought of that smell when I ate the frozen fish sticks that my mother gave us.

I thought of the bluefish eyeball my father gave me after gutting his catch, one summer day.

You can freak out your friends, if you’re a ten-year-old girl with an eyeball in a baggie.

Maybe they won’t be your friends for long, but hey, you’re tough. You’re not even scared of fish eyes. (They watch but don’t judge.)

I remember how icy quarts of milk fell like bombs from the windowsills of the nearby welfare hotel in winter.

Its occupants, or their inheritors, sleep on the streets now, cold milk a forgotten luxury. The welfare hotel’s a fancy dorm.

As for my own jewelry, such as it was, it must have been stolen by one of the demolition guys when we had work done on our apartment.

Somehow, they seemed all right. I trusted them. I forgot I had to hide it.

It was pretty much all easy come, easy go, all but my great-great grandmother’s antique mourning ring with the onyx and tiny seed pearl.

I’d been wearing that thing on a chain around my neck since my father died, but maybe the time for mourning was over.

It had been years, about five of them. My mother had a new boyfriend, an architect, a lovely man who could never stop fixing things.

Another time, a ridiculous tenant next door tried to do his own wiring, and the firemen came with their axes to save us from the flames.

There weren’t any flames.

There was no fire on our side of the common wall, just a good amount of smoke.

But we weren’t home, and they had to be sure. It cost us our front door, quite a lot of plaster, plus an old marble mantlepiece.

These things are the price of living in close adjacency with other humans.

With the comfort of the crowd—the freedom, the safety, the anonymity— comes some jostling.

For me, the street is still the safest place because of that public gaze.

The danger’s in the corners and the thresholds, the crossings over, public into private, private into public.

Like our neighbor who was stabbed as she entered her brownstone’s front vestibule.

My mother’s boyfriend replaced the photovoltaic sensor lights my father first installed. No shadows to lurk in on our stoop.

Which reminds me how a friend got held up with a toy gun on the best but leafiest, dimmest, street in our neighborhood.

Whatever became of you, Byron Shambly, after going up for assault and robbery with a Hasbro product.

I’ve had a gun pointed at me, too, right in my face, in Brooklyn.

The perp was the defense attorney. The gun was in an evidence bag. I was Alternate Juror Number One.

The accused, a guy I’ll call Shahim, he (allegedly) threw the gun away.

It came back to him, thanks to the Sanitation Department’s new initiative: recycling.

My favorite witness for the prosecution worked for Waste Management, where he sorted the gun right into his waistband.

Cline, let’s call him, was arrested waving that same gun at a 7-11 clerk.

He went up river and was living in Ossining when the real crime was done. Quite an alibi.

The ballistics came back. Looked like Cline was just the vector.

Shahim, the virus, walked. I’d like to think he wouldn’t have, if I’d actually been on the jury.

Maybe he was too scary to send to jail. (They read out the jurors’ names and addresses in open court!)

Our neighbor, she survived the stabbing because the Sears Roebuck catalogue she’d just picked up off her stoop was so thick.

It deflected the knifeman’s thrust.

I got this appalling mailing from Restoration Hardware. What was it, 700 pages? Criminal. And straight to recycling.

At least we have recycling now.

I grew up in Brooklyn, before there were surveillance cameras but after there were beat cops.

My dad taught me how to walk on the streets of New York City: Fully aware.

Don’t walk inside scaffolding or tightly parked cars. You could be cornered.

Know who’s on the sidewalk with you, and across the street. Look them directly in the eye. They will choose another victim.

If you hear hoots or whistles when you turn a corner, change your route.

It may be a signal among thieves.

Keep a fake wallet with just a few dollars in it to give to your mugger, so you don’t get fleeced when you’re held up.

Hold your house keys so one protrudes through your fist as a weapon.

And have your keys ready before you approach your own door. Enter quickly, and look behind you before you do so.

(You might not have a catalogue handy to save you.)

Exiting is safer, because you come as a surprise to the passersby, popping out your doorway, unexpected.

I remember how we propped the door of our building open, when they carried my father’s body out, zipped up in Naugahide.

We left it open, and all day and night a stream of mourners came and went, bearing casserole and flowers.

The next one in the building to die was the fourth-floor tenant.

We smelled him and called the cops. They responded fast, like it was a homicide.

They were about to bust his apartment door down — to do what, resuscitate the maggots? — when I found the landlord’s key.

He was face down, bloated, by his filthy bedside, lying in a slick of fluid.

The other thing that struck me was that this guy did not recycle. There was a three-foot-high drift of Popov bottles in the front room.

Two cops watched me and my mother’s boyfriend clean up the mess the coroners left. Did you know maggots flee from bleach?

Then they sealed up the door with yellow tape. Just in case, you know, there was evidence of a crime.

Crime is down since the seventies. So are deaths at home.

And my kids are growing up in Brooklyn, in the very same building, I did.

I’m thinking they’re ready for their own keys. Jagged Medecos.

It’s not the seventies anymore. I know I don’t have to worry like my father did.

Still, I’m going to teach my kids the rules. Just in case.

If you live in Brooklyn — or anywhere else for that matter:

Separate your trash.

Use a licensed contractor.

Be fully aware.

Leave your apartment door unlocked.

Follow the Brooklyn Rules.